Solar geoengineering might work, but local temperatures could keep rising for years

Professors Patrick Keys, Elizabeth Barnes and James Hurrell co-authored this piece for The Conversation, based on their recent research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Colorado State University is a contributing institution to The Conversation, an independent collaboration between editors and academics that provides informed news analysis and commentary to the general public.

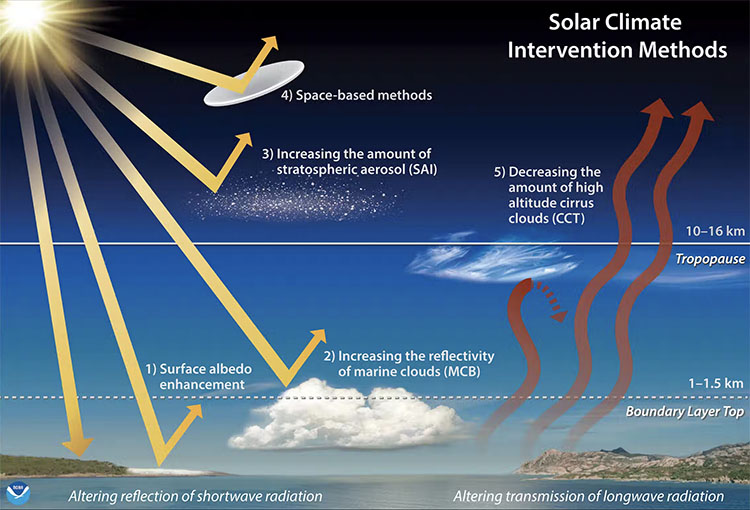

Imagine a future where, despite efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly, parts of the world have become unbearably hot. Some governments might decide to “geoengineer” the planet by spraying substances into the upper atmosphere to form fine reflective aerosols – a process known as stratospheric aerosol injection.

Theoretically, those tiny particles would reflect a little more sunlight back to space, dampening the effects of global warming. Some people envision it having the effect of a volcanic eruption, like Mount Pinatubo in 1991, which cooled the planet by about half a degree Celsius on average for many months. However, like that eruption, the effects could vary widely across the surface of the globe.

How quickly might you expect to notice your local temperatures falling? One year? Five years? Ten years? What if your local temperatures seem to be going up?

As it turns out, that is exactly what could happen. While modeling studies show that stratospheric aerosol injection could stop global temperatures from increasing further, our research shows that temperatures locally or regionally might continue to increase over the following few years. This insight is essential for the general public and policymakers to understand so that climate policies are evaluated fairly and interpreted based on the best available science.

Read the full article, “Solar geoengineering might work, but local temperatures could keep rising for years.”

Graphic: Some potential methods limiting the amount of solar energy in the atmosphere. Chelsea Thompson, NOAA/CIRES